Published by Leidybos įmonė “Kriventa” (2017)

On a fine Lithuanian day in 2006, I got a surprise. Working at the American Center in Old Town Vilnius, a city full of the ghosts of history, I was pleased to have one of the best jobs in the whole of the Foreign Service. As a public affairs officer and cultural attaché, it was a relief to work in a place where almost everyone openly liked Americans. In a world full of unhappy misperception, I faced just the exact opposite in Vilnius: here instead I had to manage expectations of what we were actually capable of doing. We were not just a benign new Western version of the Warsaw Pact after all. So it was in my daily routine to meet a stream of enthusiastic petitioners—young, old, academics, activists, parading in with bright new ideas of big things that we could do together. Seminars, art exhibitions, music recitals, film festivals; you get the picture. In other words, I was thoroughly used to people asking me for things.

I met photographer Saulius Paukštys when I first came to Vilnius. He had lent our Center an exhibit of his photographs of Vilnius city, all shot from a hot air balloon. By this time in 2006, before the great global recession, Vilnius was flush with energy, creativity, and optimism, having finally hit its stride as a free and proud European capital. Modernity was rampant, but in good architectural taste, as everyone well-knew that what often fascinated not just tourists but also investors, was the seeming unspoiled beauty of what some called “an undiscovered Prague.” By no means did this imply that Vilnius had lived its long history as an untouched, untrodden backwater–just the exact opposite. In Lithuania one often hears its people boast that they lie at the geographic center of Europe. As a result, Vilnius was massively and historically trodden on over the centuries by waves of boots and tank treads, from the Teutonic Knights of the 14th century to occupation Soviet tanks in living memory of older siblings and parents of today’s millennial generation. The 20th century’s horrors fell hard on the peoples of Lithuania-Jewish, Polish, Lithuanian, and Roma—yet through it all managed to leave much of the city’s architectural legacy intact.

This heritage is best discovered by roaming the cobbled streets and the smooth, stone-paved Town Hall Square, or the wide avenue named for founding father Grand Duke Gediminas, that runs from Cathedral Square to the Parliament. From a medieval castle tower named for the duke, past a modern theatre, opera house, music academy, hotels, shops and bistros, the streets recall all Lithuania’s aspirations and hard history, the light and the dark, as along its thoroughfares remains the somber presences of the KGB building, now a museum to Soviet oppression, and the now peaceful but once tormented passageways of the Vilna Ghetto. In his photo exhibit Paukštys captured all this, but in a new angle–from a bird’s eye.

Hot air balloons over Old Town by 2006 had become as ubiquitous as they are over Cappadocia, and it became a cheering sound to me to hear the breathy snort of the balloon burners outside my hillside apartment windows overlooking the preserved baroque, gothic, and renaissance streets of Vilnius. Like colorful, friendly, aerial leviathans, these wicker basket flying conveyances were the best way to see the city, a genius way truly. Aside from an occasional fiery, levitating hot air blast, the balloons are totally silent, the better to see daily life on the streets, the denizens of Vilnius unaware of being watched unless they happened to look up. I was unsurprised to hear that in Lithuanian the word for “bird” is “paukštys“.

Another thing I liked about Vilnius was that just around the corner from my flat was a vest pocket park, and in it a statue to one of my hometown heroes, rock god Frank Zappa. I come from an immigrant town in America, a working port city, and it was a big surprise to stumble across old Frank, iconoclast, nonconformist, a left field composer, and free-speech activist. I knew that in the Iron Curtain days, before the Internet and YouTube, it was possible to cut off entire countries from knowledge and culture from beyond the border, and especially from across the sea. All the same, ideas get around. In those days, by radio, television signal, and even cassette tapes, music did cross borders, and free-spirited ideas with it. Even in the U.S., Zappa was seen by many as rather subversive, and definitely as anti-establishment. In this light, Zappa and rock at large can very well be said to have had a democratizing effect, loosening the grip of authoritarian rulers on the minds of society. If a statue to Lenin could be replaced by one of Lennon, then perhaps the KGB had known what they were talking about when they found rock to be a threat.

So it was that one afternoon on my agenda Saulius Paukštys had made an appointment to see me along with two of his friends. Aside from being a talented artist, I knew Paukštys was prime exponent of the “independent republic” of Užupis, a quirky little corner of the city, a short walk away from my Old Town office, across a narrow bridge festooned with padlocks, each of which proclaimed the eternal love of couples whose initials and names were engraved thereon, memorializing loves meant to last at least until rust set in or keys were fished from the river. Užupis, its entrance decorated with a striking statue of a trumpeting bronze angel, had been championed by Paukštys in years past as a place that aimed to be a Lithuanian Left Bank, or a Vilna River version of Denmark’s bohemian counter-culture Christiania.

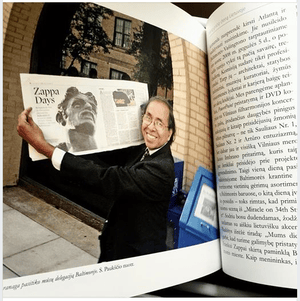

Artist Paukštys I knew too as spokesman for Vilnius’ Frank Zappa Fan Club, the people behind the raising of the handsome, rugged pony-tailed Zappa bust atop its shining brushed steel pillar. But it was some years before I arrived that it was raised, as a publicity stunt perhaps, but one that in retrospect made perfect sense as an expression of solidarity with artistic freedom everywhere. I had grown up listening to Frank Zappa and other classic rock bands of the 1970’s on the FM radios of urban America. That my new friend Saulius had found inspiration in the same things I had as a young man I found heartening. Having lived his youth behind the Iron Curtain, he truly got it, that freedom is at its core the power to remake oneself and one’s world at any moment, not in a lost past or in a never to come future, but now.

Awaiting my visitors in my Pranciškonų gatve (Franciscan Street) office I felt a quiet satisfaction in that moment, sitting at my big wood desk, gazing out the window on the courtyard, the same view that some Middle Age abbot once had, knowing my center’s long vaulted auditorium was likely once dining hall to monks. My grade school nuns would have been pleased. Still, I had no idea what Paukštys had on his mind that day. It was late afternoon when he came with his friends, arts promoter Arturas Baublys, and Saulius Pilinkus, Vilnius Town Hall director. As we settled down for our meeting I was already going through my mental checklist of reasons to gently but appreciatively say no to likely requests for even small sum grants to jumpstart all sorts of bright ideas that I was sure they’d be presenting. Niceties deployed and introductions made, Paukštys began by recapping the story of the Vilnius Zappa statue. “Here it comes,” I thought, “He wants me to arrange a music festival and bring in an American band perhaps,” or, “He wants me to find a way to help him organize a Zappa film festival,” FZ having been an avantgarde film director of some repute in addition to having been a gifted musician. I paused in my thoughts long enough to hear Paukštys say, “I want to gift a copy of the statue to the United States.”

“Come again?” I asked–this time aloud, and listened for the inevitable catch. “Yes, we want to give to USA a copy of our monument, to show our respect for Zappa and the people of America.” Quickly I think and respond, “It’s very wonderful and generous Saulius, but this will be a very expensive gift,” imagining the cost of actually reproducing a bronze bust replica, its 4-meter high steel column, shipping it to the U.S., then finding someone willing to go to the expense of procuring a suitable site, surveying it, landscaping it, and actually installing the artwork; definitely not in the scope of my small grants budget. “No problem, Carlos,” the affable madman Paukštys boomed, “We will get donations!” Imagining the work, I thought, “Gulp.” I replied, “And where do you propose putting it, Saulius?” Of course he said, “We leave it to you!” I smiled, he went on, “Maybe we give it to the city of Zappa’s birth—Los Angeles!”

In the course of any bright idea, a tipping point is reached, like a peak past which the rising momentum of what’s proposed takes over. I then remembered how in my first language, Spanish, roller coasters are called “montañas rusas” or “Russian mountains”, yet in Russia a roller coaster is called “amerikanskiye gorki,” or “American mountain;” either way, a big hurdle. “Wait,” I said, “Zappa wasn’t born in L.A.–he was born in Baltimore.” Every Baltimore boomer knows that well, and that’s what I was–a Baltimorean.

In recollections of my high school days, are memories of submarine sandwiches from Hasslinger’s Deli in northeast Baltimore, served up by a gentleman we knew as “Old Man Zappa,” FZ’s uncle. Even though Frank and his family left Crab Town before he’d hardly finished middle school, by gosh, we all knew he was no joke from our parts and we were proud of it. I gently pointed this out to Paukštys, quickly adding that a statue of this size in a city like L.A., with no discernible center, would soon be lost to public notice as a mere roadside attraction of a rank order between Marilyn Monroe’s grave and the La Brea Tar Pits.

To this logic Saulius simply said, “Okay, to Baltimore!” to the assent of his companions, Art and Pilinkus.

So began the process of turning this into reality. For me it began by sending an e-mail to Baltimore City Hall. To the two Sauliuses, Arturas, and their band of Vilnius artists fell the hard work of making a pipe dream come true. First they lined up the studio of Konstantinas Bogdanas, the original sculptor. By this time he was 80 and had plied his art since the middle of the last century, deep in Soviet days. Then came a long stretch of fundraising that proceeded at times with the pace of a poorly attended bake sale, but at other times was simply brilliant. My favorite was the grandiose Vilnius philharmonic hall concert of covers of favorite Zappa tunes by the Vilnius Brass Quintet. Their haunting, plaintive take of Zappa’s slow waltz chanson “How Could I Be Such a Fool,” off his 1966 album “Freak Out!” literally made the hair on my arms stand up in awe. Fools maybe, but divine fools; making beautiful music from originals that maybe once were seen as low camp and adolescent, or instead so inspired as to appeal mainly to music snobs. In that instant it became plainly clear to anyone with functioning ears that the Zappa oeuvre had withstood the test of time and entered the realm of the classics. The Kronos Quartet could eat our dust.

I left Vilnius, abode of the arts the next year, on the conclusion of my assignment, but by no means was I free of the quest to see the project to its end. Back home to Maryland and Baltimore, a city not unlike Lithuania, full of yin and yang, light and dark, quirky and crazy, bright, sad, and oppressive. On the credit side of the ledger was its cultural history of savants, artists, and visionaries. A short list would include the Sage of Baltimore-reporter, writer, and chronicler of American language and society, H.L. Mencken, he of the acerbic wit and observer of a long gone time in the city’s pre-World War II history. He was like a written word Zappa. And there was the dark genius of Edgar Allan Poe, of “Nevermore” and “Rue Morgue” fame, progenitor of the Baltimore NFL franchise Ravens moniker. On the musical score we had so many that one could go on at Wikilength, but just to render the flavor, one can toss out names such as Billie Holiday, Eubie Blake, David Byrne, and Philip Glass; then were the film makers typified in their range by bookends John Waters and Barry Levinson. Though Zappa left the city young, Baltimore’s DNA is discernible in him to any clear-eyed observer. He was a native son who left not just his hometown much too soon but his home world altogether, when he departed this vale way too young, at 52 in 1993.

Then there is the dark. “The Wire” was set in Baltimore for a reason. There’s lots to be said for the city in which I grew up, but an honest assessment cannot ignore the poverty and alienation among those left behind economically after decades of trickle up economics, and oppressive racial and class divides with roots deep in the history of the nation itself, a distrust that pools in places just like Baltimore, as it does in other struggling towns and cities across the land. Suffice it to say that Baltimore officialdom had a lot more on their platter than dealing with generous obsequies from offbeat Lithuanians come bearing gifts.

My first exchange with Baltimore City drew interest from the staff of Mayor Martin O’Malley. His staff was polite but made no commitments. When they left for the governor’s mansion the next year after he was elected chief executive of Baltimore’s state of Maryland, our effort went effectively back to square one as an entirely new mayoral crew took up shop. Files were bequeathed to staffers of new Baltimore mayor Sheila Dixon, and after months of back and forth discussing notional sites, the project gained its first practical champion in the person of Kim Domanski, public arts coordinator at Baltimore’s Office of Promotion and the Arts. She asked for blue prints and all manner of technical details with which to make an official pitch to the Baltimore City Public Arts Commission. It was they who would decide if the city would accept the gift, and if yes, then give the green light for finalizing a suitable site. It was May 2008, even as the new statue was already cast and awaited word to come before being shipped from Vilnius.

But for this to happen the Commission had to meet, and for this purpose, Paukštys and crew decided to cross the Atlantic to make their case. They landed at Baltimore-Washington International Airport on May 5, 2008 and the hearing was to be held that Wednesday. The commissioners were a true cast of worthies, with architects, structural engineers, museum curators, distinguished community leaders and retired legislators among them. We prepared portfolios, a PowerPoint, and DVD copies of the Vilnius Philharmonic concert demonstrating the fullness of feeling of the donors, which by this point consisted not just solely of the enthusiasm of Saulius #1, #2, and Arturas, but also now the full imprimatur of the counterpart Mayor of Vilnius who had also chipped in a nice chunk of cash to the venture. So after a day of touring Baltimore’s waterfront sights and sampling the worth of Baltimore pubs, the hearing came to order, with the gravitas of the court scene from “Miracle on 34th Street.” In a basso profundo stentorian and heavily Lithuanian-accented voice, Paukštys intoned, “We are honored to have a chance to present this Frank Zappa monument to the city of Baltimore. As an artist, and more than that, he has meant a great deal to the Lithuanian people. Frank Zappa was a voice of freedom.” Like a cruise missile down a chimney, Saulius’ words had their desired impact. The commission voted unanimously to accept the gift. “Zany Lithuanians to Donate Zappa Statue” and “What’s New in Baltimore” (also presciently, the title of one of Zappa’s best remembered songs) were some of the U.S. headlines that day. But in a city where potholes take years to fix and that truly, had lots more fish to fry, the moment’s enthusiasm for the gift meant neither the statue’s immediate shipping from Vilnius, nor any speeding of the planning process.

After long months of deliberating and reaching out to Baltimore neighborhoods to see which might be most suitable and open to hosting the statue, we were down to a short list: Patterson Park, the fresh air lungs of East Baltimore and one of the finest city parks in America; Baltimore’s Arts District near Amtrak Penn Station, the Maryland Institute College of the Arts, and Meyerhoff Symphony Hall; and a site near century old Lithuania House, a rickety but character-filled old-style immigrant social club with a retro bar and basement dining room that each Friday served up Lithuanian specialties like the baconladen potato dumplings known as “cepeliniai” for their likeness to zeppelin airships. It was also home to the one-of-a-kind, annual “Night of 100 Elvises,” a festival of Presley tribute acts. Not much more Baltimorean than that. One by one the neighborhood groups looked straight in the gift horse’s mouth, and gave it a pass.

One thing always awesome to note about Frank Zappa was his propensity for being an autodidact. It was as if he could teach himself anything. A prodigious composer, he taught himself musical theory without the encumbrance of formal training. Zappa famously said about formal higher education, “If you want to get laid, go to college; if you want an education, go to the library.” So it was that in December 2009, after more than 18 months from the time Saulius had made his appeal to the public arts commission, that the library returned the favor to Zappa, when Baltimore’s Enoch Pratt Free Library system stepped forward to offer the Zappa statue a home in front of its brand new Southeast Anchor Library branch on Eastern Avenue, amidst the store fronts, and white marble stepped painted screen window Baltimore row house blocks just east of Patterson Park on the main street of working class district, Highlandtown.

With this development, the momentum became unstoppable. And though Mayor Dixon left office under a cloud of legal indictments–nothing to do with Zappa– the next mayor, Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, took up the baton on beat. That’s when the project’s next Baltimore angel stepped up to bat. Jeanette Garcia Polasky on the new mayoral staff, a long-time Zappa fan determined to see the thing through and done right. By now the project had in fact gathered a host of angels, like Roswell Encina, PR director for the Pratt; Cindy Klebeck, Anchor library branch manager; John Richardson, Pratt’s facilities management chief; Hillary Chester, of the Southeast Community Development Corporation, and many, many others.

Back in Lithuania, Saulius and crew had not been simply playing the waiting game either. In the months before the commission had arrived at its happy conclusions on the statue site, Vilnius hosted Dweezil and Gail Zappa during Dweezil’s summer 2009 European “Zappa Plays Zappa” tour. The finished Zappa bust replica, a precise copy of the Vilnius vest pocket park original, made its first public appearance at the Vilnius municipality building with the Zappa family on hand during their lightning 24-hour concert stop there. With the Zappa family firmly onboard, and throwing in behind the effort, the Baltimore team entered into discussions with Gail, keeper of the Zappa family flame, on just how to do it up right.

In early 2010, the time had come for the Zappa bust to cross the wide waters. The revolving door nature of Baltimore mayoral politics no doubt slowed things down. But then that was not much different from Vilnius in this way. Unlike Vilnius however, Mid-Atlantic coast Americans are big snow wimps, so when Baltimore and its region were hit by successive blizzards and a 55 inch accumulation of snow, the treads of government definitely were slowed as non-essential personnel stayed home and none but emergency workers ventured on the streets. Lithuanians would look as askance at this as would say, Minnesotans. With much ensuing hard work on both sides in the months following, the day at last did arrive that I got word via a Baltic News Service dispatch, “Frank Zappa bust from Vilnius leaves to Baltimore, MD.” The wire read, “2010 June, 10. 13.00 hrs, Vilnius Town Hall – After 3 years…replica of FZ sculpture leaves from Vilnius, Lithuania to Charm City…Attending (were) Saulius Paukštys, and Saulius Pilinkus authors of the idea, US Ambassador in Lithuania, Vice mayor of Vilnius and sculptor Konstantinas Bogdanas among others…Bust has been packed and loaded…All were in a mood of joyful and glorious moments, photo session followed." Champagne went unmentioned, no toasts were quoted, but I for one raised a glass.

The bust and its pillar were loaded on a boat on the Baltic Sea, and made landfall July 19 in the port of Baltimore. It cleared customs and was stored in a cavernous southeast industrial warehouse owned by the city. When I arrived to be on hand for the unboxing on August 3, I swear I caught a glimpse of the crate with the Ark of the Covenant from “Raiders of the Lost Ark” nearby. Crowbar and hammers in hand the crew pried loose the fasteners one by one until like a creaking door opening, the lid gave way to reveal the bust, nestled and bundled in protective packing. We eyeballed it the best we could, and it was perfect. Frank Zappa Day was set for Sunday, September 19, 2010, a resonant date that also happened to mark the 25th anniversary of Zappa’s 1985 Capitol Hill testimony supporting free speech by recording artists before a Senate hearing generated by prominent D.C. political spouses to pressure the record industry into affixing warning labels on music content. With Zappa on that day, testimony opposing free speech restrictions was given by recording artists John Denver and Dee Snider of the metal band Twisted Sister.

Zappa Plays Zappa’s managers, Clearpath Entertainment, in a press release gave Gail Zappa’s sentiments on the confluence of dates, “Frank’s legacy rests in his uncompromising defense of the First Amendment and his uncompromising pursuit of excellence clearly demonstrated in the standards he set in all areas of music and the arts and sciences associated with it. He was self-taught and self-realized. It is hard to imagine how that is possible except for the four cornerstones he had going for him: a talent for music, a hard-core curiosity, a keen sense of humor and access to a library. He was a cheap date for History.”

Dweezil’s band headed the line-up of activities which included the Zappa family speaking to their fans Sunday morning at the Creative Alliance before the unveiling. In front of the library, the bust now stood wrapped up in its preparatory white shroud, traffic was diverted for the inaugural ceremony and street festival, and food hawkers began to sell shaved ice snowcones laced with limoncello, dubbed “yellow snow”, recalling a famous Zappa song on what not to normally eat while carrying a lead filled snowshoe.

The Lithuanian contingent came to town of course, Paukštys and crew, and Vilnius Mayor Vilius Navickas in tow. What could have been more perfect? A clear late summer day, and time for a celebration, with a host of local worthies taking the stage, including Mayor Rawlings-Blake and Pratt CEO Carla Hayden. Hayden was later named the U.S. Librarian of Congress, the top library post in the U.S. Paukštys arrived wearing a yellow, green and red Lithuanian flag on his shoulders, like some Baltic superman. But leave it to Gail Zappa to put it in perspective, as she explained, “When they asked me where this statue should be placed in Baltimore, I said, ‘Let’s find a community library.” So there you have it, the legacy of Frank Zappa come home to roost from a far place where people again had gained control of their own destiny, and with that power had chosen to exercise it with humor, generosity, and gratitude for their freedom.

Now we know what’s new in Baltimore. As Zappa’s musical lyrics put it, “Better go back and find out.”